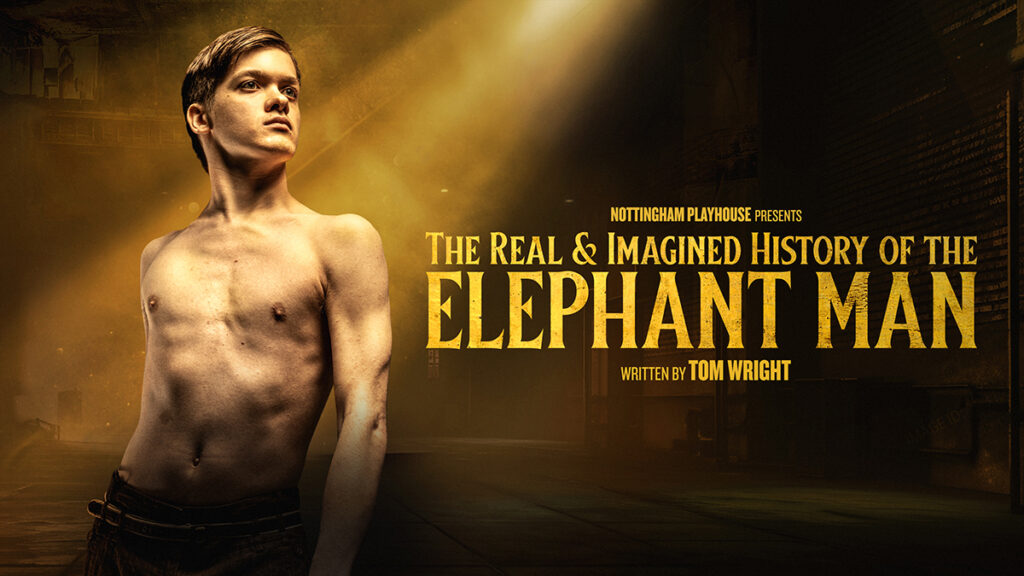

Zak Ford-Williams is taking on the challenging role of Joseph Merrick this autumn in ‘The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man’. The tour starts at the Nottingham Playhouse this month.

Interview by Tom Jamison

How are the rehearsals going for ‘The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man’?

Really good. It’s really starting to knit together. I’m very excited by what it’s shaping up to be. Sometimes you get a feeling in your gut about certain projects, that they’re going to go well, and it’s one of those.

What’s it like to rehearse with an all-disabled cast?

Great. Going to drama school, and in almost every other project I’ve been involved with, I’ve been the only disabled person. You do the things you have to do as a disabled person, in making everyone else comfortable with you. It’s been really nice not to have to do that and to be around more disabled people. I didn’t grow up around many other disabled people, so it’s been fantastic to experience that. And they’re such wonderful people and such staunch professionals, they’re brilliant!

Would you suggest then that the process of rehearsals for this production hasn’t been so much adapted, as much as universal?

Yes. Stephen Bailey (director) said, something that I really liked, relating to why he decided he wanted lots of disabled people, because otherwise we’d all have to have loads of conversations about what’s it like to feel different and what’s it like to be different. But we all know that. We all understand that as a baseline. We don’t have to have those sorts of imaginative journeys or conversations.

Oddly, there’s nothing on the promotional materials for the play about it being an all-disabled cast…

There’s one of us who isn’t disabled, and his character is very pointedly not disabled.

I don’t know how much I can speak about that… It was a deliberate creative choice.

How does your cerebral palsy affect you day-to-day and as a professional? Acting is a physical job and it’s a physical role…

It’s a hugely physical role. I get tired very quickly. A lot of my prep for this was stamina training and physio, just to make sure I could physically do it. It is a straight run of Joseph (Merrick, the lead character) on stage. So, I get very tired, it can get difficult to control my speech. It’s really funny, I’ve had to do a lot of speech therapy and what have you. Learning how to control my speech and spending hours and hours in my room practising how to make my mouth do what I want and my body to do what I want.

I think there’s a slight advantage, because I’m so used to being very aware and having to control my body and my mouth. When I have to change my physicality or my voice I have, I feel, a great awareness to begin with, to then construct something else.

I’ve also never used BSL before. We have an actor who uses BSL. And Joseph’s using BSL. So, I’m sort of learning a new language. The character is learning BSL to try to communicate with a person who’s around him a lot. So that’s been really interesting; learning your lines and then learning how to say them in a new language at the same time.

You deliberately refer to the character as Joseph, rather than the ‘Elephant Man’, but even so the role comes with a lot of baggage doesn’t it? It’s problematic isn’t it?

It is. To put it nicely, I’m not the biggest fan of the ‘Elephant Man’.

What I loved about this script, and what surprised me when I read it is that Joseph is not a saint-like figure, trapped in a body. He is an angry, bitter, lonely man, who then finds himself and he hates that. Also, it’s not just critical of the streets of Leicester and the people. It’s critical of the care system and medicalisation that was in place.

One of the things that I love is, when he’s been put in the freak show, and when he is being examined in front of all the lecturers at the hospital, he calls the staff monstrous. He hates it. I love that.

As a disabled person you must have (like me) been in a situation whereby the consultant comes in and asks if you mind the students having a look at you…

This is why we’re all in the cast; different disabled people with different bodies. It’s all about perception, because I’m doing it as myself, without prosthetics. It’s all about our perception of difference.

It’s really interesting, actually. It’s a really lovely drawback of having loads of disabled people in a room. We’re learning to look at me as Joseph nastily, because we’re disabled people and we’re used to difference, but we’re playing characters that are not used to difference. I love how the hospital is presented in this play. It pats itself on the back all the time – and they’re awful, and they don’t understand him and make no effort but to medicalise him. There’s something that really rings true about it, which is different from any other adaptation I’ve seen. Frederick Treves (Merrick’s doctor) is not even a character in this. It’s all the people he interfaces with, Treves wouldn’t have talked to this man. Frederick Treves’ book was the inspiration for the (David Lynch) film. Well, there’s a lot in the book that means that what we think we know about Joseph’s life may or may not be true, particularly the fact that he calls him ‘John’ throughout the book, and his name is Joseph. Treves casts himself as the saviour; it’s a very Victorian surgeon sort of thing. His account is not part of this play, and I think he’s mentioned once and Joseph says, I don’t remember him.

You sound very satisfied that this version is so different. As if you’re writing a wrong, almost.

Yes. I feel that and I think part of the weight of this project is that I count myself a lucky disabled person, with a voice and autonomy. There are a lot of disabled people who don’t have that. And Joseph, in this play, is someone without that, and part of the way I feel is that I’ve got to do justice to him and to those other people.

There’s a fantastic line in the play which really simplifies this for me, because he’s sort of stopped speaking, he retreats within himself and someone asks him why, and he says, ‘People ceased speaking to me, so I found I had less and less to say in return’. People stopped talking to me as a person, so I just stopped. It was pointless.

What about Zak within all this? There must have been challenges in becoming a disabled actor. And there must be ongoing challenges in being a disabled actor as well.

It’s interesting, I saw a play at the theatre when I was five and I went home and decided I was going to be an actor. And I never changed my mind. My parents, bless them, have always sort of stuck by me.

I’ve spent thousands of hours practising but that can feel quite isolating. I think this is part of the reason I connect with Joseph, in that sense. Disabled people, I think, can understand that sense of sealing yourself off and finding the strength. It can feel like no one else understands.

What will you take from this rehearsal and production process?

People have generally been open, and even when they’ve not, minds can often be changed, but you pick your battles. Disabled people will understand that you often have to fight for your place and your position. I wheel into a room and get those reactions – because I’m young, people think, we know why you got this job. There’s a thing of ah, yes, he won’t be very good. There’s this assumption behind the eyes, so you feel like you constantly have to prove yourself. What’s been nice about this project is that I don’t have to bang my head into the metaphorical brick wall repeatedly to try to earn my place. I’ve got a real sense of belonging. It’s nice.

The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man’ is at Nottingham Playhouse

Sat 16 Sept to Sat 7 Oct

All performances are presented in a relaxed environment and all performances are captioned and audio described.

For further details and to book tickets, visit: www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk

The tour continues at: Blackpool Grand Theatre

Tues 17 Oct to Sat 21 Oct

Belgrade Theatre, Coventry

Tues 24 to Sat 28 Oct